The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

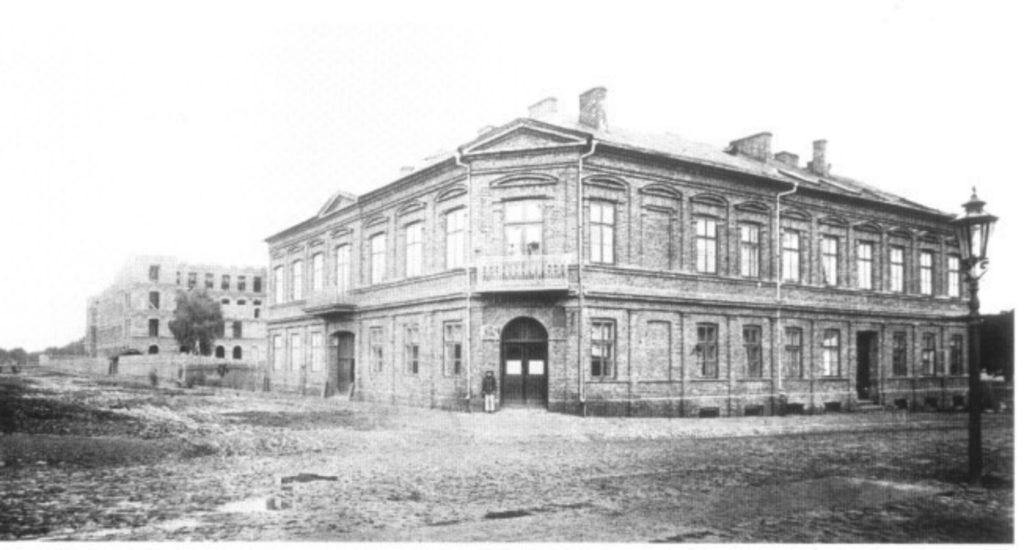

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,

school, hospital, and even a church – in times of glory it all resembled a true ‘state within state’. In less than half a century, Izrael Kalmanowicz Poznański changed from a lowly merchant, who contributed a manufactory worth merely 500 roubles into his marriage with Leonia Hertz, into a powerful factory owner with 11 million in his account.

In 1877, Poznański bought a multi-storey, brick-built house together with detached buildings: a ground-floor dyeing mill, wooden outbuildings, a square and a garden at the intersection of Ogrodowa and Stodolniana (today Zachodnia) Streets. The compound was then extended and the palace itself was modernised during three main renovations. Despite the common opinion, it did not originate as a residential building: its main intended use was its representative and commercial function with a residential part, designed by the contemporary city architect, Hilary Majewski, based on models of the French Neo-Renaissance. The residence was surrounded by a huge garden, with the total surface area of 4,255 m², which expanded from Ogrodowa Street to Drewnowska Street, all the way up to the bed of the Łódka River. The part situated in the closest vicinity of the palace was a strolling garden, the farther one was functional: a vegetable garden with greenhouses, conservatory, shooting range and pond.

Interestingly enough, until today we can admire in that garden the greenery that remembers the family strolls of the Poznańskis. The enormous diversity of the plants that grow here – nearly 60 species of trees, shrubs and vines that appear here – is a characteristic feature of the palace garden. Among them, there is the yellow-leafed ‘Worley’ sycamore and an absolute rarity in the form of two unique strains of maple. Their peculiarity is testified by the fact that they do not have Polish names and they cannot be found in Polish dendrology companions. According to Professor Romuald Olaczek, they are true botanical phenomena, freaks of nature of a kind, differentiated from the typical representatives of their species by the shape of their leaves. The current form of the garden diverges considerably from the original design, however, the following elements have remained here up to the present day: part of the old tree stand, architecture of the current drive, rotunda, and stairs leading into alleys. Also the gas lanterns in the form of statues of guardians holding torches have survived up till today.

The palace earned its current form as a result of a few modifications introduced along with the changing financial status of the Poznański family. The first redevelopment took place in 1898, according to the design of Juliusz Jung and Dawid Rosenthal. The decision about the next redevelopment was taken in 1901, already after Izrael Poznański’s death (he died in 1900, at the age of 67). The enterprise of extending and decorating the interiors of the palace fell to his sons: Ignacy, Maurycy, Karol and Herman. On their recommendation, the project of extension that imparted its Neo-Baroque form to the palace, was designed by Adolf Zelingson, Maurycy Poznański’s schoolmate. The architectural supervision over the works was exercised by Franciszek Chełmiński. The works were completed in 1903. It was when the residence earned an architectural form similar to the present one.

The residence was supposed to highlight the status and the financial possibilities of the Poznański family. The building is dominated by domes, which hide a representative Neo-Baroque dining room and a ball room. The sculptures that crown the frieze of the facade are inspired by the iconology of the Italian renaissance humanist Cesare Ripa, who described the most important symbols of the era in his book. The designers drew inspiration also from similar residences of the financial bourgeoisie of western Europe. The thirty-six two-metre figures on the roof of the palace symbolise the power of the contemporary industry, trade, wisdom, and success; in their hands, they are holding attributes of hard work: cogwheels, bales of fabric, chains, hammers, etc. Among them, we can find workers, spinners, Hermes – the god of trade, protector of merchants, and Athena – the goddess of wisdom and art, adept at weaving.

In the main body, which performed a representative function, on the first floor, apart from the Large Dining Room and the room on the first floor, there are numerous lounges, and on the ground floor, in a pavilion directly connected with the palace, there were office and stock-exchange rooms. Downstairs the side wing, there were warehouses where ready products were stored and on the first floor, residential apartments, guest rooms as well as a winter garden covered with glass domes.

World War I and its economic consequences, especially the closure of commercial outlets, as well as the wrong policy of the company’s management and the authorities of the reborn Polish State interrupted the period of successes of the Poznański Family. Although it formally still remained the property of Cotton Products Joint-Stock Society of I. K. Poznański, the palace had new users and the family was no longer interested in maintaining it.

Since the times of the World War I, the residence was rebuilt multiple times and it often changed owners. In January 1927, the Voivode of Łódź, Władysław Jaszczołt, obtained ministerial approval for transferring the Voivodeship Office from its previous seat in the former ‘Bristol’ Hotel at 11 Zawadzka Street (currently, Próchnika Street). In the 1930s, the winter garden was eliminated and some of the interiors were rebuilt.

In September 1939, the Palace was requisitioned by the German Civil Administration: on 10 April 1940, the supreme authorities and the main departments of the District of Łódź (Regierungsbezirk Litzmannstadt) were transferred to the building. After the war, the Palace became the seat of the Voivodeship Office once again, and in 1950 – the seat of the Praesidium of the Voivodeship National Council. After the war, in late 1940s, the side wing of the palace was expanded. At the end of the 1950s, a transversal wing, where today the Tax Office has its seat, was built on. The newly erected part caused the original surface area of the strolling garden to shrink.

Since 1975, part of the residence of the Poznański Family has been the seat of the Museum of the City of Łódź (up to 2009 known as the Museum of the History of the City of Łódź). Since the very beginning of its existence the institution has been rebuilding, renovating, renewing and preserving the residence, out of concern to re-establish the building to its former glory. As a result of preservation works and taking over subsequent historic rooms of the Palace, the rooms largely regained their original appearance.

Since 2017, Izrael Poznański’s Palace has been undergoing a thorough preservation renovation.

The Palace – the culmination of the 19th-century empire of Izrael Poznański, called ‘the cotton king’, was built as part of an enormous factory and residential compound, typical of the industrial architecture of the 19th century. Factory, lavish residence, houses for workers,